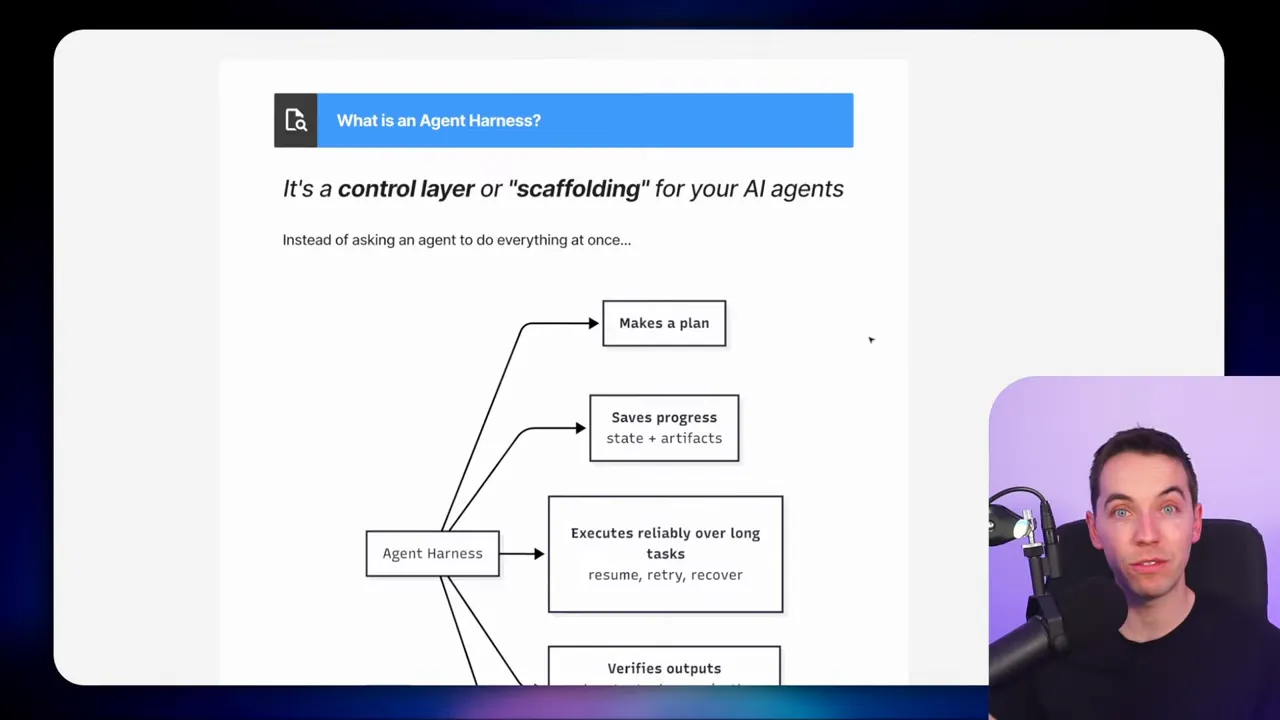

I created an automation that turns short lived AI calls into long running, reliable agents. These agents can research, synthesize, and produce reports that span hours and many data sources. The trick was adding a control layer, which I call an agent harness, around the AI so it can plan, persist progress, and resume work until the job is done.

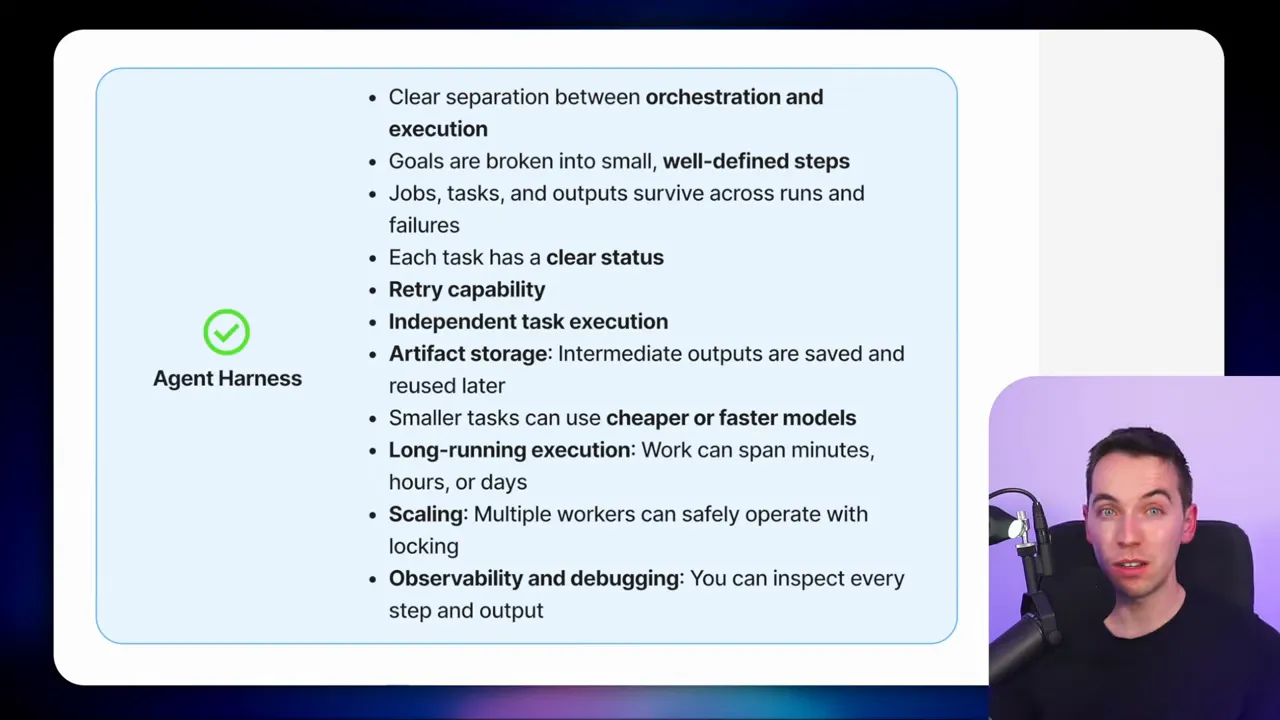

Why an agent harness matters

Most lightweight agent demos handle one-off tasks well. They answer a question or generate a short reply. Real projects rarely behave that way. A quarterly customer review, a competitive analysis, or a long audit need multiple steps. They require pulling structured data, reading meeting notes, summarizing transcripts, and combining everything into a single narrative. A single LLM call cannot hold all that context.

That is where an agent harness helps. It is a scaffolding layer that separates planning, execution, and memory from the LLM itself. The harness lets the agent break a goal into tasks, persist task state and interim outputs externally, and coordinate execution over time. With this structure, agents can run for hours or days while keeping work traceable and recoverable.

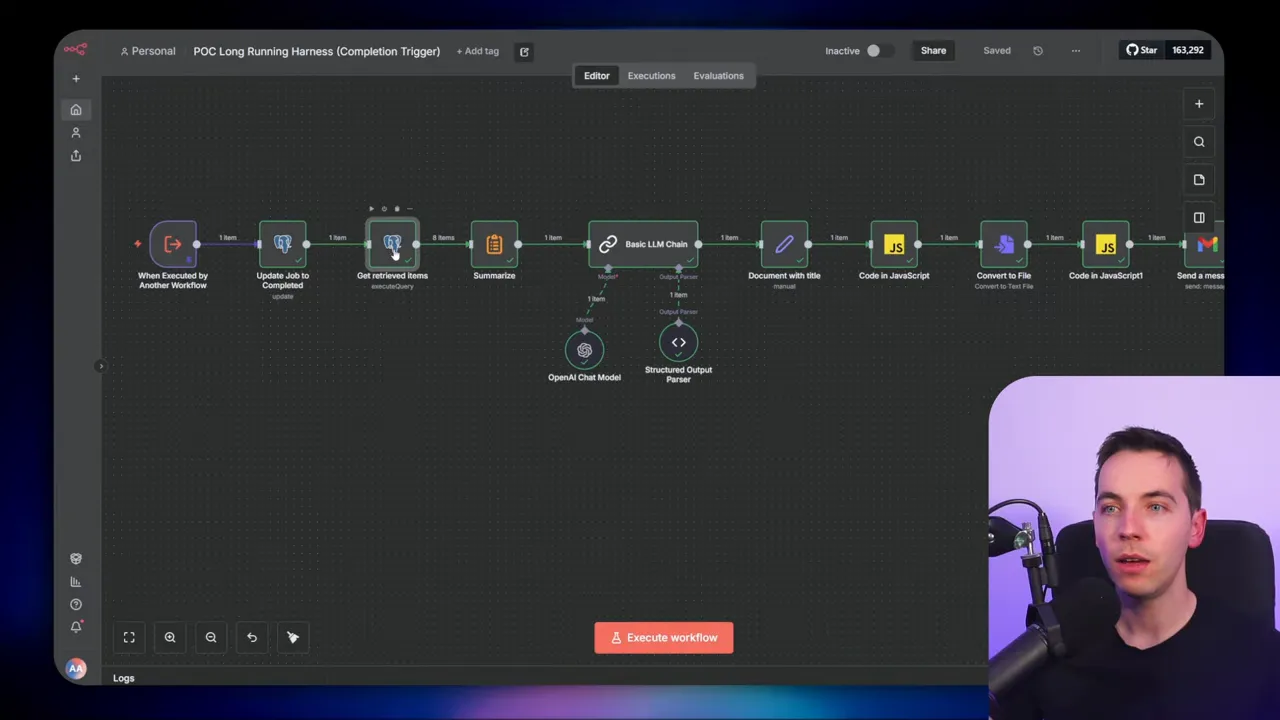

Two-stage architecture I use

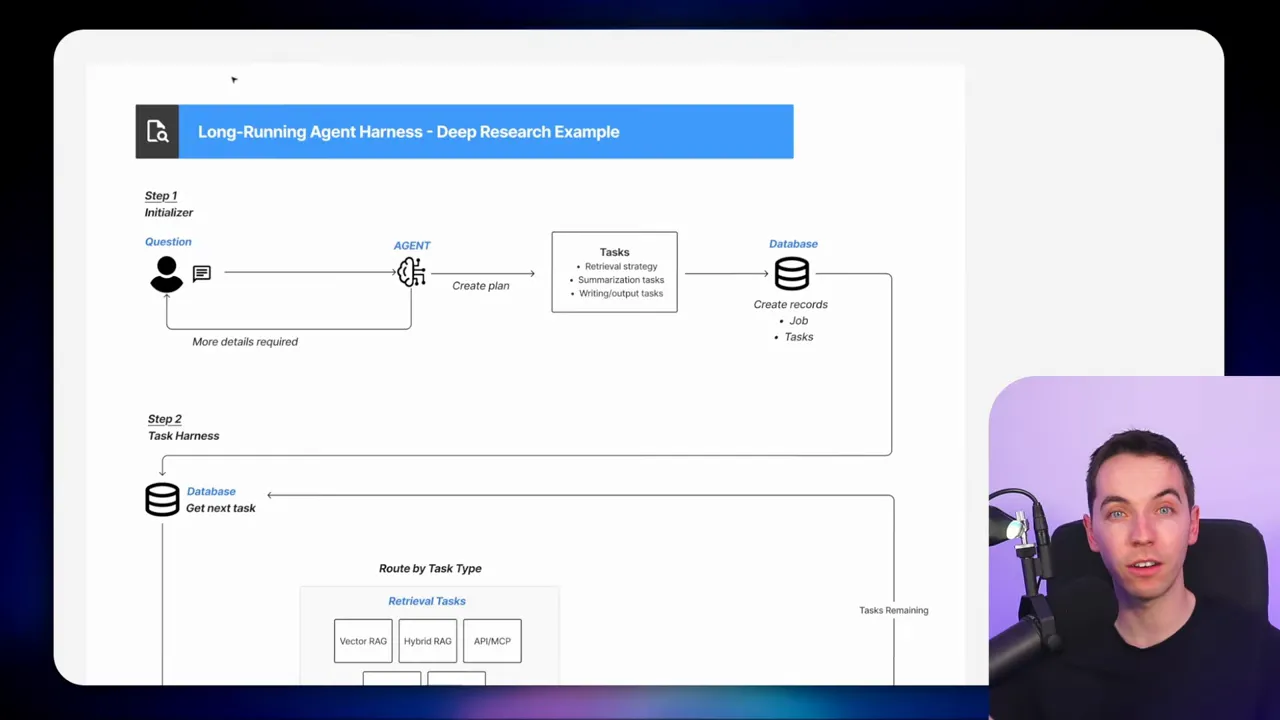

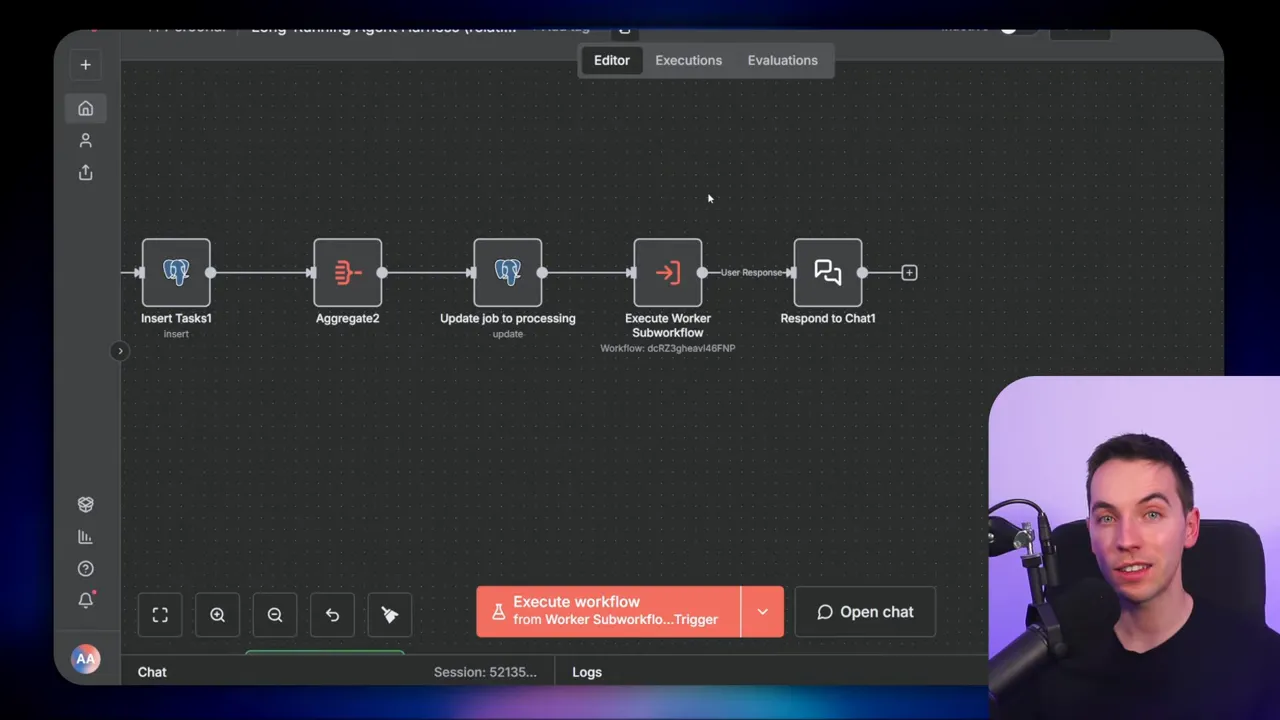

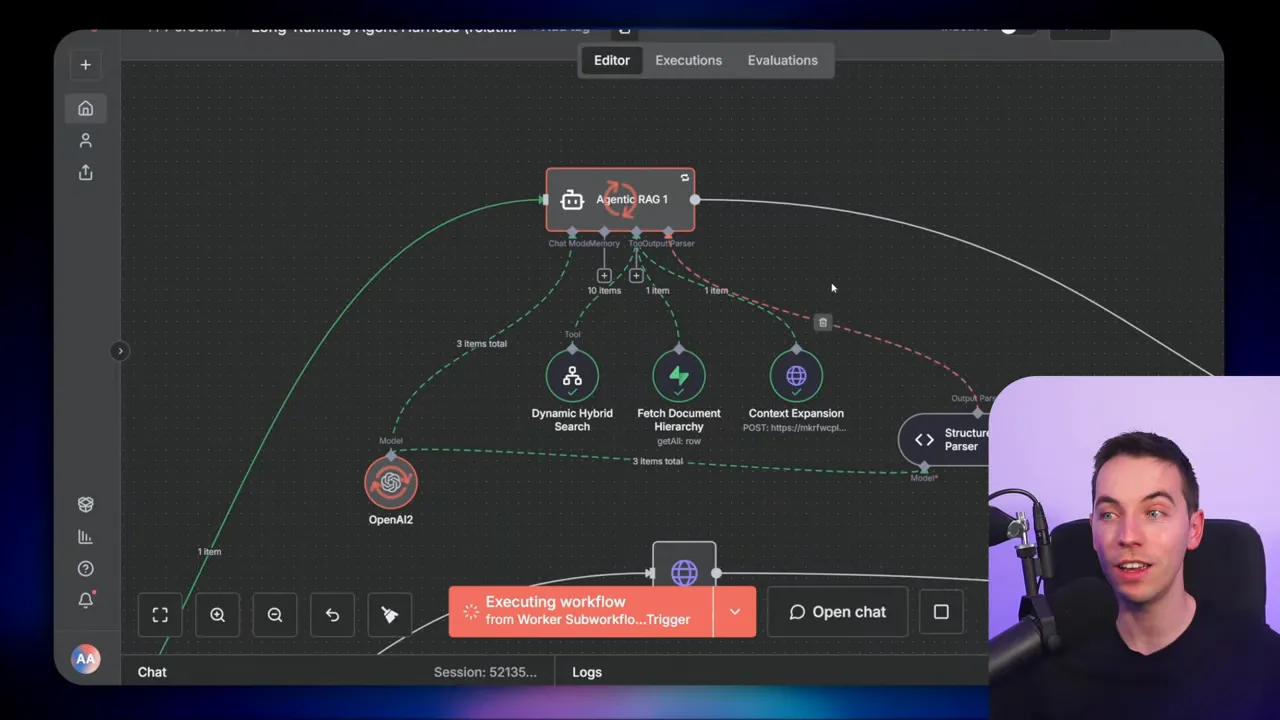

My approach is inspired by a two-stage pattern: an initializer plus a task worker harness. The initializer creates a plan and a list of tasks. The task worker then picks tasks, runs them, saves results, and moves the job forward.

Initializer

Initializer

The initializer receives the user’s request and validates it. It asks clarifying questions until the requirements are clear. After that, it produces a structured plan that lists retrieval, summarization, and writing tasks. For one quarterly review I ran, the initializer generated 22 tasks for a single customer and quarter.

The plan also includes a retrieval strategy and priorities for data sources. That helps the task worker know where to look and why.

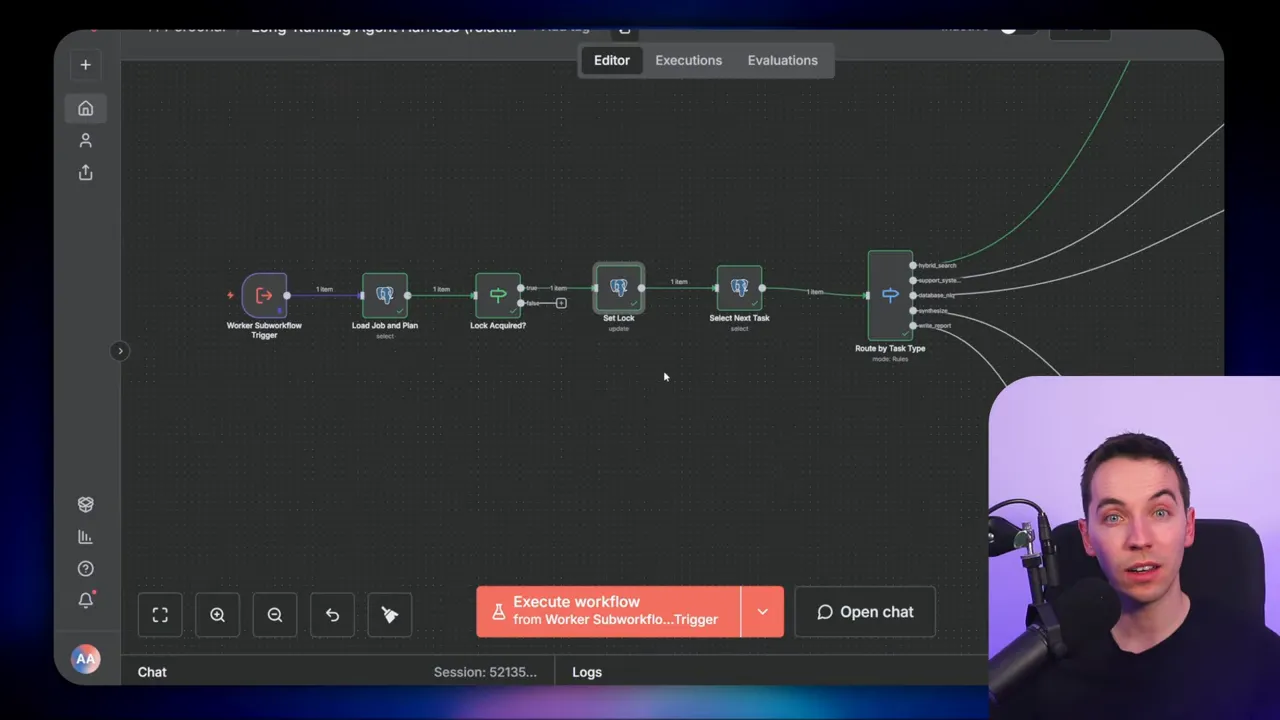

Task worker harness

The task worker is a sub workflow that executes one task at a time. Each invocation of the worker:

- loads the job record

- checks and sets a lock

- selects the next available task

- routes it to the correct handler based on task type

- stores any artifacts

- marks the task complete

- loops or finishes

Using this model, each run is short and focused. That lowers the risk of timeouts or memory issues. It also makes the system easier to monitor and retry selectively.

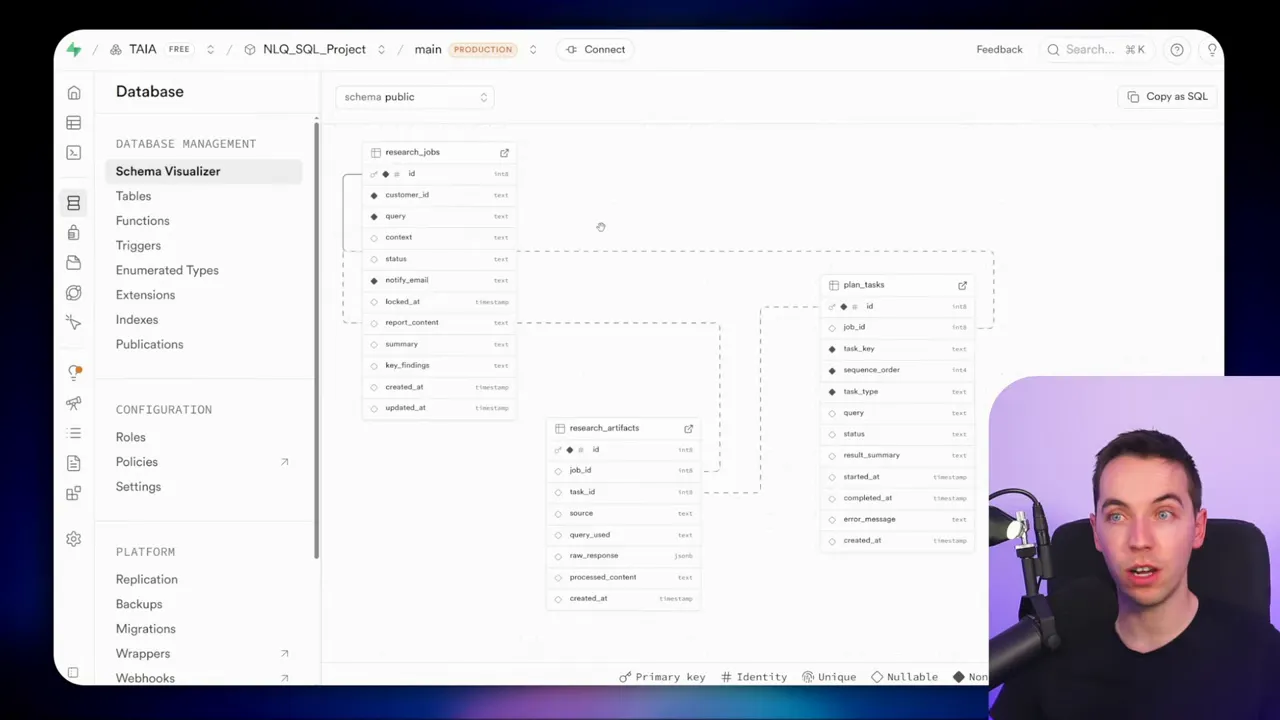

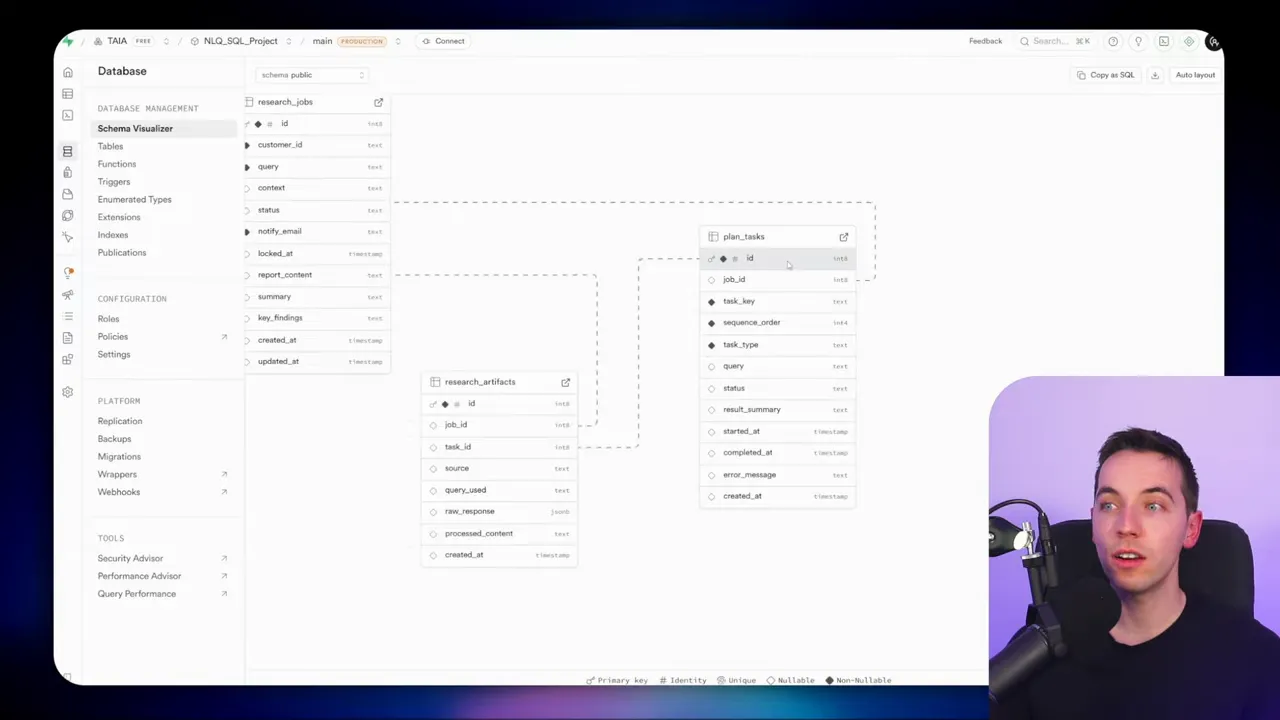

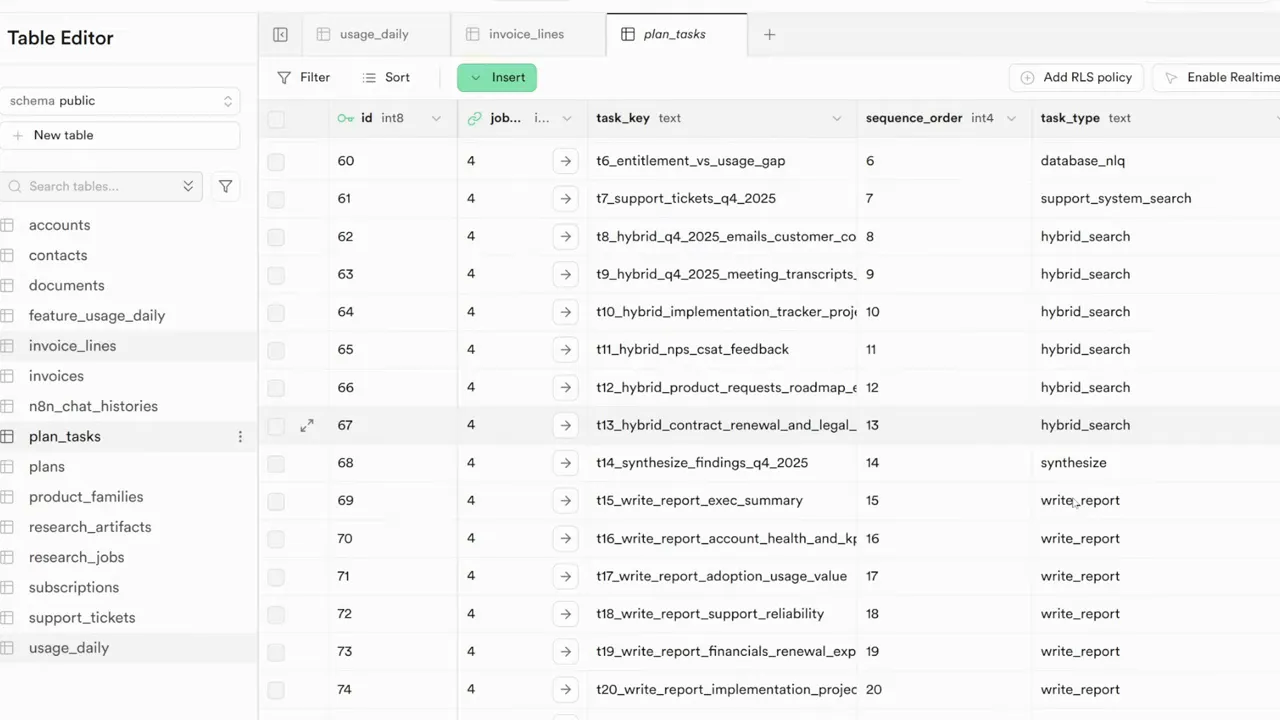

Database schema I used

I chose an SQL database to store state and artifacts. The schema is simple yet effective. It gives a transparent view of progress and allows complex queries. The three core tables are:

- research_jobs – one row per project or job

- planned_tasks – one row per task, with status, type, priority, and dependencies

- research_artifacts – interim outputs, snippets, and synthesised summaries

The job row contains the original user query and some meta fields such as current status and a lock timestamp. The task rows are the operational unit. Each task has a type like database query, support ticket retrieval, hybrid search, synthesize, or write report. The artifacts table stores what the agent finds and creates. Summaries and partial writes live there until the final report is assembled.

This structure supports multiple important features. First, it makes progress auditable. Second, it allows partial re-running when a single task fails. Third, the artifacts act as a staging area for progressive summarization.

How tasks are executed

Each time the task worker runs, it locks the job to prevent concurrent workers from stepping on each other. Locks include a timestamp so other workers can skip or reassign stale locks. After locking, the worker queries for the next uncompleted task. It then routes by task type and executes the corresponding handler.

Retrieval tasks usually involve calling external systems. I used an HTTP node for support tickets, an NLQ agent for database queries, and vector search plus hybrid search for transcripts and meeting notes. The NLQ agent has visibility of the database schema and can build SQL queries. You can restrict this access with parameterized queries or read-only credentials to reduce risk.

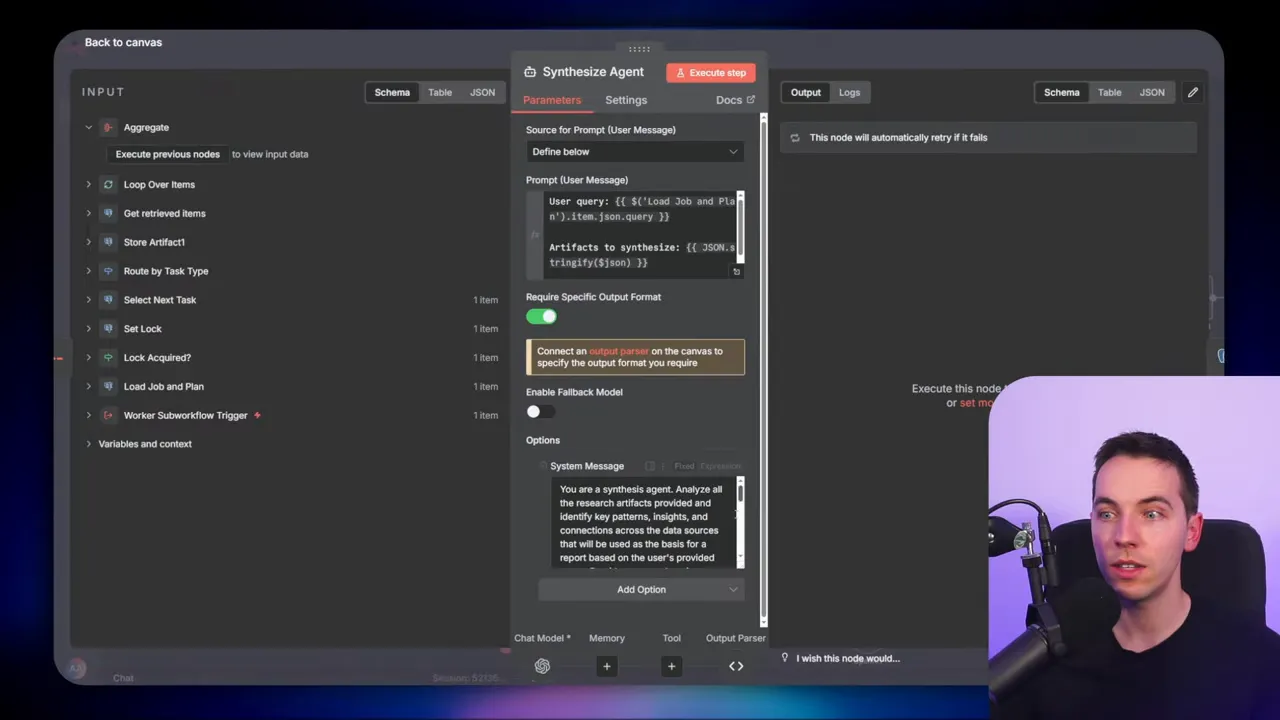

Synthesization tasks

When raw retrieval tasks produce lots of artifacts, synthesization groups and condenses them. I limit the amount of context fed into the LLM at once. In practice, I batch 10 artifacts per synthesis call. Each synthesis run produces a cleaned, referenced summary that goes back into research_artifacts. If contradictions appear, the synthesizer flags them and includes sources.

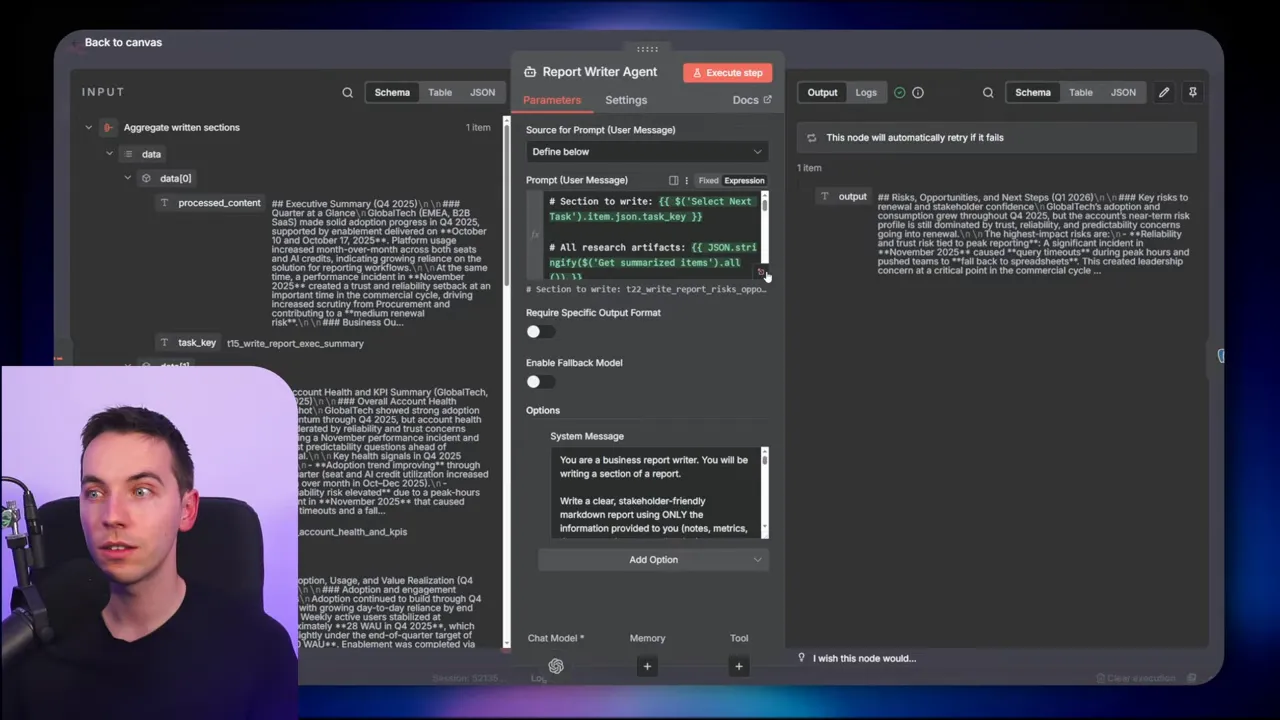

Write report tasks

At the end, write report tasks pull together synthesized artifacts and any previously written sections. The writer agent receives the target section plus context. It can use progressive summarization to include rolled up summaries of earlier sections, or it can receive the full context if the document size permits. Final outputs are stored as artifacts and then concatenated into the delivered file.

I converted the final markdown to HTML for email delivery, but you can output PDF, DocX, or any other format. The harness does not force a particular output format. It just ensures the writing stage has consistent, trustworthy inputs.

Retrieval patterns and context expansion

Different retrieval routes are required for comprehensive research. I mixed four retrieval methods to increase coverage:

- SQL queries against structured tables

- Support ticket APIs

- Vector search for fuzzy matching on meeting notes and transcripts

- Context expansion to fetch whole document hierarchies where needed

Context expansion helps when a matching chunk lacks surrounding information. It fetches related chunks or the whole document to avoid missing context. Each retrieval writes an artifact describing the source and relevance. This practice makes synthesis more accurate because every summary can list its sources.

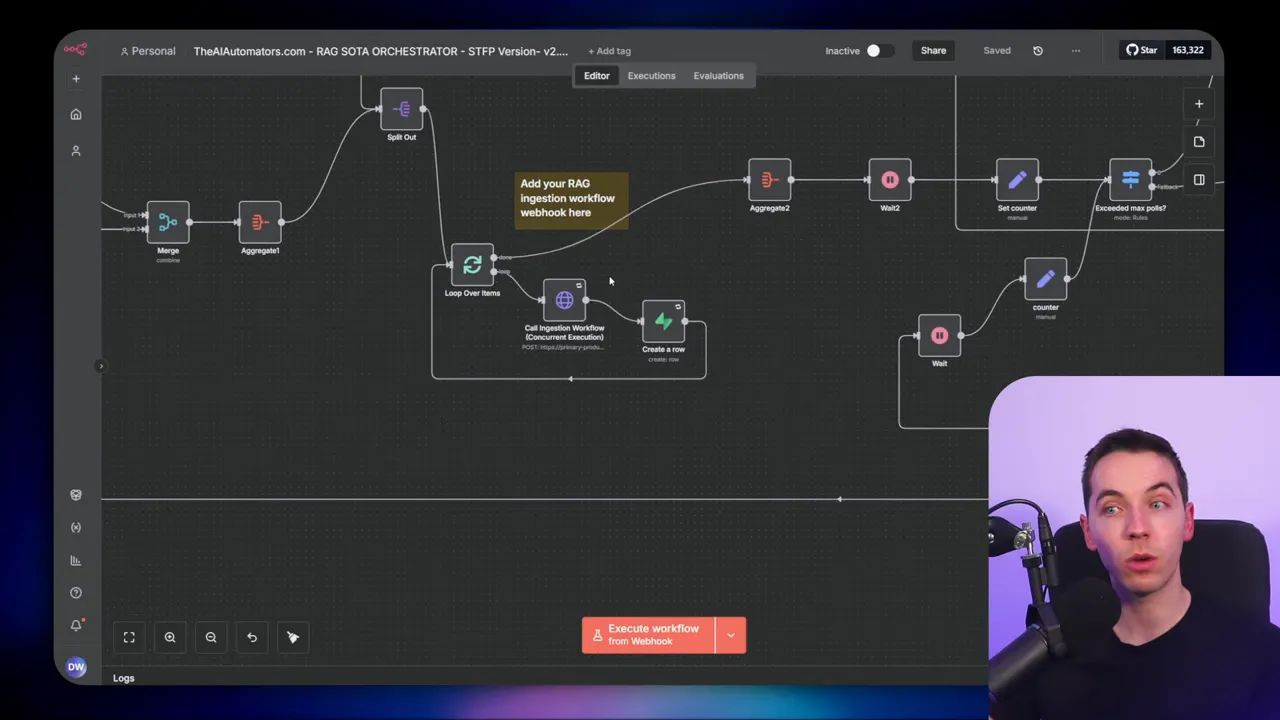

Concurrency and orchestration options

Not every part of a project needs to run sequentially. Retrieval is often the heaviest and most parallelizable step. I split orchestration responsibilities to enable a hybrid approach:

- A main task worker coordinates task selection, locking, and status updates

- A retrieval orchestrator batches retrieval tasks and fires many workers in parallel

- Synthesization and writing remain mostly sequential to avoid context conflicts

For heavy ingestion scenarios, I used batch sizes of 50 to 100 files and then triggered ingestion workflows rapidly. These workflows ran in parallel against different workers. The orchestrator tracked retries and failures, and it marked retrieval tasks complete only after successful artifact storage. This allowed the main task worker to treat retrieval as a single step even when it consisted of many parallel operations.

Queueing and worker pools can be used to control parallelism. That prevents overload and keeps cost predictable.

Five design questions that shape an agent harness

When building an agent harness, five high level questions determine the architecture. I use these to make design choices that match the use case.

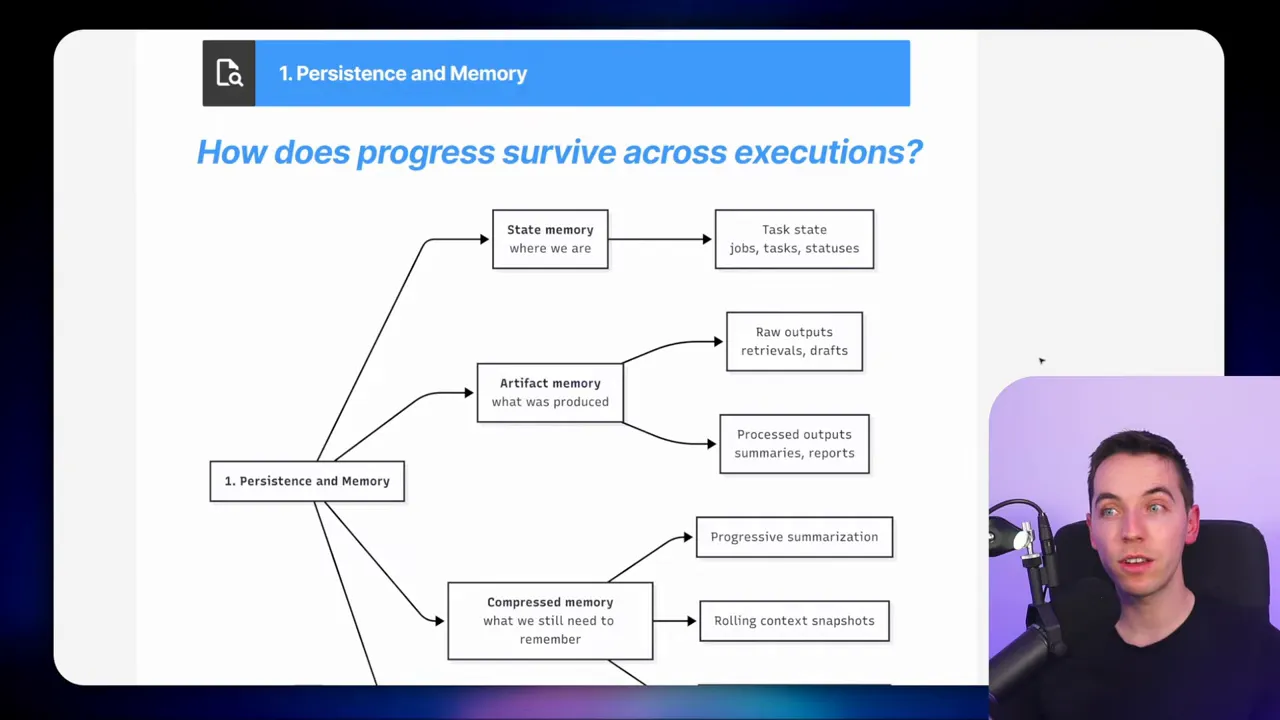

1. Where does memory live and how is it structured?

Persistence is central. I separate two kinds of memory. The first is state memory, which describes job and task metadata. The second is artifact memory, which holds retrieved data and intermediate summaries.

Decide whether to store memory in plain files, JSON fields, or relational tables. I prefer relational tables for auditing, querying, and reliability. Add compressed memory through progressive summarization. Older outputs get shorter representations as the job advances. Checkpoints are useful. Periodic snapshots let you roll back to a known state if something goes wrong.

2. How is work decomposed and updated over time?

The initializer can produce a static plan with a fixed set of tasks. That is simple and predictable. Alternatively, you can use a rolling plan that re-evaluates after each phase. A goal driven plan continually asks, what is the next best step to reach the goal? That approach requires robust guardrails to avoid infinite loops.

Test driven loops are powerful when you can define objective checks. Automated tests can tell the agent whether a draft meets minimum criteria. If a test fails, the agent repeats or adjusts steps and continues.

3. How are tasks run?

Choose between a long lived control loop and short, repeatable executions. I favor short executions that persist progress to the database. Each run picks one task and then exits. This avoids long running process failures and makes retries straightforward. It also allows multiple workers to operate safely under a locking scheme.

4. How will the system decide when work is complete?

Completion can be set by rules. The job may finish when all tasks are done. You can also require the LLM to pass a verification check. Claude’s coding agent uses test based checks to ensure outputs meet functional criteria. A human sign off adds another safe stop condition.

Automatic tests, external validators, and human in the loop options let you reduce premature success claims by the agent. These measures increase trust in the final output.

5. How many units of work run at the same time and are there dependencies?

Coordination matters. Options include pure sequential execution, parallel processing, and hybrid models. Dependencies can be represented as sequence numbers, JSON fields, or separate relation tables. I often model dependencies explicitly so a task waits until its parents finish. That turns the plan into a directed acyclic graph when needed.

Patterns you can reuse

From my experience, three patterns cover most use cases.

- Sequential task worker

Works well for small projects with tight dependencies. Initialize a plan and execute tasks one after another. Use locking and checkpoints for safety.

- Concurrent retrieval orchestrator

Use this when retrieval can be parallelized. Launch many small workers to fetch data from different sources. Aggregate artifacts and then synthesize sequentially.

- Goal driven loop with periodic replanning

Start with a high level intent. Execute tasks, then re-evaluate and adjust the plan. Include guardrails and a budget to prevent unbounded execution.

Each pattern has tradeoffs. Sequential flows are simple and auditable. Concurrent flows boost speed. Goal driven models increase adaptability at the cost of complexity.

Practical tips I applied

- Lock with timestamps: Make locks expirations short enough to recover, but long enough to let a task complete.

- Store artifacts with source metadata: Always capture where an artifact came from and when it was retrieved.

- Batch synthesis: Limit context per synthesis call. Ten artifacts is a good starting point.

- Use parameterized DB access: Limit what the NLQ agent can run. Parameterized queries reduce risk.

- Implement retries and error handling: Build a catch all that retries idempotent steps and reports persistent failures.

- Make outputs testable: Add simple validation rules. They help halt work when outputs fail basic checks.

How I assembled the final report

When all write report tasks were complete, the harness assembled the outputs in order. I used a summarize step to concatenate sections. Then a small LLM chain generated a filename and H1 heading. The document lived as markdown first, then it was converted to HTML for email delivery.

You can skip conversion by asking the writer agent to output HTML directly. That saves a conversion step. If you need richer outputs, convert markdown to PDF or to DocX once the final text is available.

Observability and cost considerations

Agent harnesses make operations more visible. You can query the planned_tasks table to see what remains. You can audit research_artifacts to confirm which sources influenced the report. This transparency helps both debugging and governance.

Cost also benefits from harness design. By controlling what gets sent into the LLM and batching requests, you reduce token expenses. Parallel retrieval consumes compute, but it often shortens wall clock time and reduces cumulative LLM usage by minimizing repeated context sends.

When to choose an agent harness

An agent harness is a strong choice when you need:

- durable memory across runs

- safe recovery from failures

- visibility into each step

- complex retrieval across many data sources

- long running tasks that can last hours

More standard agent patterns work fine for quick answers or single step tasks. If your project needs to stitch together structured queries, unstructured text, and human feedback, a harness gives you control and scale.

Common pitfalls to avoid

- Passing too much context into a single LLM call. That leads to errors and higher costs.

- Not storing source metadata. Then you cannot verify or justify synthesised conclusions.

- Trying to parallelize everything. Some steps, like synthesis and writing, benefit from ordered aggregation.

- Omitting verification. Without checks, agents may declare success prematurely.

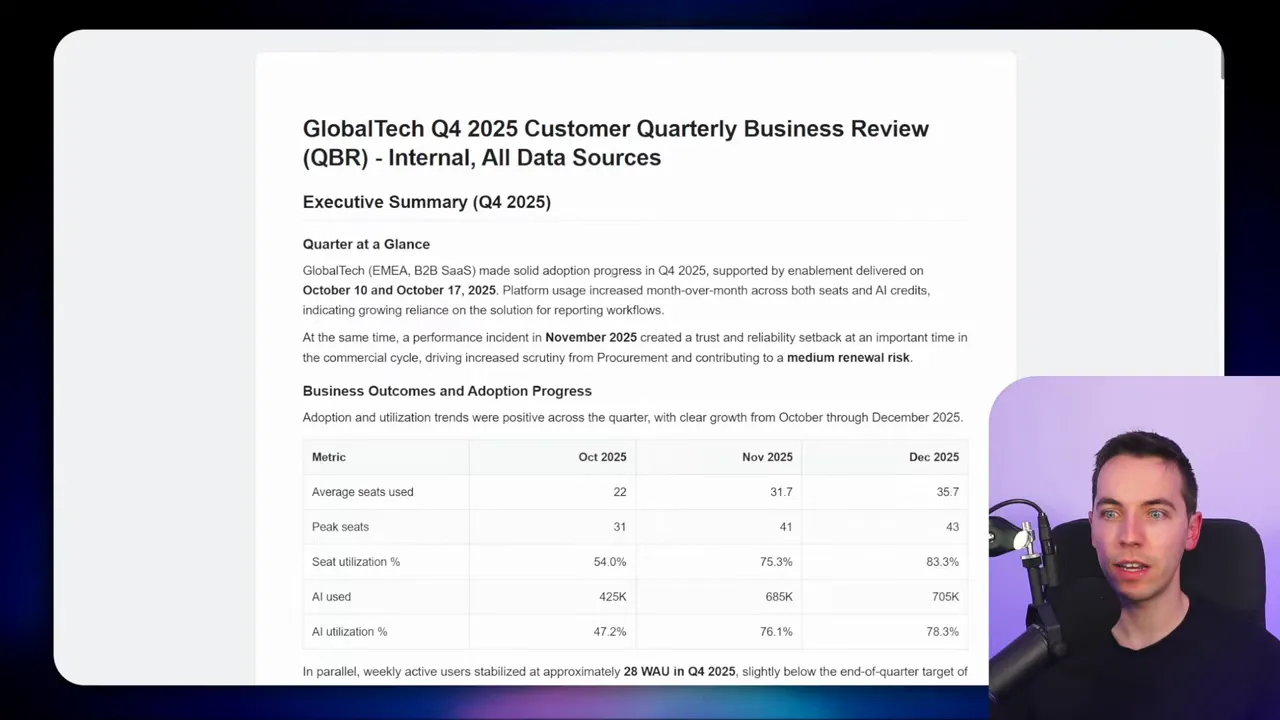

Example: Quarterly customer review, step by step

Here is a short walkthrough of the flow I built for a Q4 customer review.

- User requests a Q4 review for Global Tech and provides basic parameters.

- Initializer validates inputs and asks clarifying questions until it has enough detail.

- Initializer writes a plan with retrieval, summarization, and writing tasks.

- All planned tasks are loaded into the database and the job moves to processing.

- Task worker picks the next task, locks the job, and executes the task handler.

- Retrieval tasks fetch support tickets, invoices, transcripts, and usage data. Each result becomes an artifact.

- Synthesization runs on batches of artifacts and generates summaries that include source lists and flagged conflicts.

- Write report tasks assemble section drafts using synthesized context and prior written sections.

- When all write tasks finish, the completion workflow concatenates sections, adds a title, and converts to HTML for email.

Why this approach wins in practice

I prefer this harness model because it solves real operational problems. It makes agents reliable and auditable. It lets you recover from errors without redoing entire jobs. It supports parallel retrieval while keeping synthesis coherent. Finally, it gives you a handle on cost and observability.

Engineers have built similar scaffolds for some time, especially when context windows were small. The harness idea just formalizes that scaffolding and makes it repeatable. When a project demands deep research or long running analysis, the harness becomes essential rather than optional.